The grail is found!

After four years of intense research I

finally have found now the rider’s seat in the old academic art of

riding: (See update 15.Mai 2020)

Research Object Guérinière-Seat: Blog from mid 2016 ongoing

Since March 2016 I have used a slightly customized seat after Guérinière with some success. For this seat the rider's legs shall be held a bit forwards, "before the horse", and hold this place in most situations.

The rider's chin shall be held up and his thoracic spine pushed slightly forward, the shoulder-blades shall wander downwards a little without too much pressing them together in the back, fairly like a 100m sprinter trying to tear the finish tape as the winner.

Guérinière's basic stance furthermore contains an upright, over the withers held left fist, in which the reins are led one-handed on a sole curb-bit, with the upper rein between 4th and 5th finger and the lower rein running around the little finger. The thumb's nail is on top, the little finger at the bottom. The rein-fist stands nearly perpendicular, seen from the side as well as seen from the front, it is tilted ab. 10° to the left (supinated 10°) and this stance in riding straight forwards will be varied only minimally.

[CORRECTION 2020: At first I had thought, that the thumb always points to the front and lies parallel to the horse's spine column, but now I know that the thumb points 30° to 50° to the switch-side!].

For a bending to the left the switch will be held parallel to the right side of the hores's neck, to push the head to the left, for bending the horse to the right, the switch is held crosswise over the neck: both reinforce the outer, bending away from itself rein).

Sometimes the right rein has to be held by the right hand separately, the switch-hand is positioned lower than the rein-hand, otherwise both hands are kept on the same height and near to each other (Amendment: this only with a snaffle-curb!, see also Update 29.11.19!). To train this special seat-balance, I use the lowered switch-hand very often, even without leading the reins separately. Gueriniere's favorite curb bit was a "simple canon", a snaffle-curb with a broken bit, which allows leading s.t. with separate reins to be far more exact than with an unbroken mouthpiece.

For collection Guérinière lifts the rein-fist, and for advancing he lowers it.

My customization is, that for advancing I will push the PIP-joint (joint between proximal and medial phalanx) of the rein-fist's little finger forwards (which I call the "Pinky-Push") and by tilting this way the rein-fist backwards (as if you want to touch the middle of your forehead with an imaginary switch held perpendicular in the rein-fist): in extreme the rider then can see the base-phalanxes of the second to fourth fingers. The result is a radial (to the radius bone) kink of the wrist. In this occurs a strong tendon tightening over (radial) and under (ulnar) the wrist, reaching up to the middle of the lower arm.

For collection however I will pull the little finger backwards to my belly and by this tilt the fist to the opposite direction through this motion: in extreme, the rider cannot see the nail of his thumb anymore (as if you would touch your horse with your imaginary perpendicular held switch in the rein-fist right between the ears). This results in an ulnar (to the ell = ulna) kink of the wrist. The movement in the carpal-joint is similar to the one of the lower hand on the single paddle in a canoe during backwards paddeling,the resulting tension in the rider's back-muscles are similar, too. This movement I call "Pinky-Pull".

In both cases the thumb will hold its place, building the rotating point.

The switch-hand is held on many of his pictures, too (supination is a palm held upwards [imagine eating soup out of your hand] ) (the opposite, holding the hand of the back upwards would be called “pronation”).

Only the supination (or at least upright-standing) of the rider's hands creates the necessary space for the rider's belly to come forward (pronated hands prevent this!): I call this "the belly before the horse".

A Pinky Push of the switch-hand is possible, too, but for that it has to give up the supination and use the upright position.

The gaining in advancing happens very spontaneous: even while pushing forward the little finger it is already starting, continually like one would take pressure off a steel-spring! But the collection happens so softly, that I always need two or three steps to fully register it.

Part A of the research would initially consist in confirming the following impressions I get:

1. The advancing by the Pinky-Push is not due to bringing it's minimal weight to the forehand, rather it permits the rider's belly coming forward a little, reflexively resulting in a little pelvis-tilt forward.

2. The initiation of collection by the Pinky-Pull is mainly the result of the retraction of the rider's belly as a reflex on the pulling back of the little finger and the consecutive pelvis-tilt backwards.

3. Holding the switch hand in supination results in a little move backwards and a freeing of this side's shoulder, accompanied by an approaching of the rider's right upper-arm to his chest, restoring the equilibrium.

4. Pushing, with forwards held rider's legs, the forefeet down onto the stirrups lets the rider's heels rise up slightly and consecutively lightens the seat through taking the upper-legs' muscles away from the saddle, giving the horse's chest room to rotate freely (this must not be confused with simply pulling up the heels!).

Part B of the Research: If one or more of my assumptions in A will be confirmed by other riders, we would try to define the muscle-movement-chains of the rider's body triggered through these movements (here also orthopedics, physiotherapists, osteopaths and chiropractors probably could contribute a lot):

Possibly it could be described like this: „The Pinky-Push (tilting of the fist for advancing) leads, via a tensioning of the ulnar hand-abductors to a tilt of the shoulderblade into the ribs, with a straigtening of the thoracic spine and by this a hyperlordosing of the lumbar spine, which results in a forward tilt of the rider's pelvis: with naming all the involved muscles, their movements and possibly their opponents, too.

Or for the pronation of the rider's switch hand: „The blocking of the rider's right shoulder through a pronated switch-hand is the result of a tightening of muscle X, which leads to holding fast the shoulder-joint Y and because of that, over a tightening of the right side long muscle of the rider's back to a lifting of his pelvis on the right and with this to a pushing over to the right the rider's body above his pelvis.“

If enough riders will have tested the seat and agree to my assumptions in A, I would be glad to build a discussion platform for everyone willing to contribute to B.

Dr. Daniel Ahlwes, Schimmerwald, July 2016

P.S.: Caution: with legs held forward, you should not use your spurs there: they likely will hit the unprotected horse's elbow bone (very painful!)

Reasons for using Guérinière's Basic-Seat:

I agree to the opinion that sees the curb as a most valuable instrument. Also I think the one-handed leading of the curb reins is for most occasions the optimum (I use the two-handed leading only in special exceptional cases). My two-month test with an academic hackamore showed a similar result, so one has to assume that cavemore and even the one-handed led cavecon will be possible, too.

If, while using the single-handed rein-leading one doesn't want to work with only one dominant rein, which touches the horse's neck only on one side (as seen in the Marc Aurel statue) , but wants both reins to act with equal pressure on the horse's neck, this presets the only possible position for the rein-hand in the middle above the withers : with Guérinière for the straight or bent straight: perpendicular in the middle above the withers, the thumb pointing forwards, being parallel to the withers' length.

As now the middle over the withers is occupied already, we have to live with the fact that symmetry for the rider's upper body is impossible: we can only try to find a compensation somehow. The stance of the rein-hand constitutes a minimal supination in the left hand: this effects the approaching of the left upper arm to the rider's chest, were it stays in a relative stable position.

Supinating the switch-hand compensates this not only through freeing the right shoulder, but also by the approach of the right biceps muscle to the rider's chest, thus offsetting the effect of the left hand's supination: now the rider is sitting straight again (but not symmetrically!).

For turning the horse, the rein-fist will be tilted so, that the thumb (pointing as always to the front) wanders outside with the fist's base staying fast on the spot. The resulting minimal difference of pressure of the reins on the horse's neck results in a prompt and finely tunable turning! To support the right bending Gueriniere positions the switch supinatedly across the horse's neck and the reins to the left side, pushing the horse to the right. In the left bending, the switch is held at a distance parallel to the horse's neck on it's right side, pushing it's shoulder to the left. My future plan for self-education (under occasional, regular supervision with the high-value help for self-help by Marius Schneider, MAAR) is to train at first Guérinière's basic seat for some more months with the goal of riding at least a third of the time of each riding unit in an approximately good basic seat. Only then I will try to approach the extended seat of Guérinière: Guérinière shows on many pictures another feature: to achieve a more pronounced right-bending of the horse's neck, he uses the little finger of the switch-hand to grab the right rein: so in effect he rides with separate reins! For this Guérinière holds the switch—hand held a fists-height deeper than the left and keeps all the above mentioned features of his basic seat: he “simply” adds the grab of the right little finger into the right rein, which now runs considerably lower now than the left. Doing that the rider needs a very good command of the basic-seat and also of leading separately the snafflecurb-reins, as this very easily produces a hard and unbalanced force on each rein! If one calls his basic seat challenging already, reaching and holding for a certain time his extended seat deserves being called a little mastership, I would say! An intermediate effect is achieved by extending the rein-hand's little finger to the switch-side, pushing with it the rein more pronounced for bending.

Update August 2016:

Meanwhile I see the basic Guérinière Seat as a very reliable foundation of my riding seat, of which the most important pillars are my mostly forward held legs, the 10° supinated rein-hand and the 30-90° supinated switch-hand (the upright fist taken as the reference with 0°, from which up to 90° supination to one side and 90° pronation to the other side are possible). Sometimes still necessary bigger movements of the switch-hand can be leaned on these stable elements very precisely.

Most riders will have experienced frustrating situations through the non-reproduceabilty of certain effects on aids: if one, for example, leads the upper-arm of the switch-hand near the upper body, possibly a soft, prompt croupe-out to the opposite side is produced. Having performed this successfully 5 times, one is elated as seemingly a new aid is detected. Then sadly is doesn't work anymore over months !! The reason lies, I see now, at least to a big part in the way of placing the upper arm to the chest: in pronation it has a different, sometimes even the opposite effect than doing it in supination! Because of this I'm now trying to observe always which kind of rotation my lower arm is in: so the thrust of my switch, which I'm using as substitute for a sword/machete, at thistle-heads or bramble-twigs is getting a lot more precise and smoother in supination (like a forehand-hit in tennis or polo: in this movement the considerable capacity for outwards rotation in the shoulder joint enters the game,too!).Also toucheés to the horse's hind on both sides I perform now only with a supinated switch-hand: if ,on the bent side, I do this around my belly to the opposite side, it will work only in this way: would I try it in pronation, my whole spine would contort and tact and movement of the horse be disturbed heavily. This pronounced rotation of the upper body I use also as gymnasticication of my switch-hand shoulder, which comes forward more and easier (and as preparation for using an instrument on the "wrong" side, too!). One has to be careful, naturally, for the rein-hand not to leave it's place over the withers, which is not easy!

The last three sentences show, that I am also still inclined to the utility-riding! The Guérinière-seat meanwhile is pure "L'Art pour l'art". Here the nicest compliment might be, that Baron von Eisenberg (1748) sometime in the future could appreciate my style of riding like he did that of the riding master von Regenthal:" I have never seen a rider sitting more stiffly on his horse or using the advantages especially of the legs better than him! It was a real joy to see him ride,....!" (In the commentary to plate 37 here on page 76).

Update 2:

Gueriniere

meanwhile was not as free in departing from the utility-riding as to abandon the right-hander-seat. Nowadays we are not so constrained anymore and allowed to use the left-hander seat, too, with changing the rein- and the switch-hand.

With this change I can avoid the problems of grabbing the right rein with the right little finger (and thus avoid riding with separate reins), because with changing the reins to the right hand, its little finger becomes much more movable for bending the horse's neck to the right, and also the switch has not the limited range of being put across the horse's neck to the left, as it is used now fully parallel to the left side of the horse's neck to enhance the bending to the right.

This means, if we allow to change freely from right-hander to the left-hander seat on demand, it is possible to carry the switch on both hands on the outside of the horse, if necessary!

Update 15. September 2016:

Meanwhile I'm convinced that for riding one-handed this seat will become the new reference-seat in the academic art of riding, against which every other way will have to be measured. Coarse, unprecise aids are discarded entirely, many aids are getting unvisible and the horse moves much more free and unconstrained: the horse's grace stays unperturbed!

Through the exactly defined basic-seat the beginner will advance much faster and the developed rider can lean at this structure changes/novelties with ease and evaluate their effects exactly.

Possibly we will reach the excellence of a Baron von Eisenberg or a Gueriniere soon and enable many more riders to execute beautiful schools in the air

Update 26.Sept.:

By applying the Pinky-Push (= pushing forward the PIP-joint of the little finger of the rein-fist) the advancing of the horse gets immensely easier (if need be in combination with a little use of the switch), so that the rider's legs can distance themselves from the horse's belly evermore and ever longer and over time the rider's heels can stay turned away from the horse for ever longer time spans. The latter leads to a turning away of the calves' muscles and to an even easier advancing of the horse (a turning of the calves' muscle towards the horse's belly now occurs only for very short times, when necessary).

Pulling up slightly the rider's heels additionally leads to a stiffening of his ankle- and knee-joints and through that to a constant distance from his balls of foot to his buttocks (the rider is standing a tiny bit in the stirrups, comaparably to "sitting" on a swivel stool).

By this a bumping into the saddle is avoided and in trot and canter a constantly comfortable seat is achieved, regardless of possibly stiff horse-gaits or possibly steep fetlock joints. A "wiping out" of the saddle doesn`t occur anymore and the rider always sits on the very same place in/on the saddle. The suspension in the rider is located now evenly in his minimally giving ankle-, knee- and hip-joints and spine-column.

Update 28. Sept. 2016:

Meanwhile the similarities between the Gueriniere-seat, with it's supinated hands, and the Lotos-Seat in Yoga become apparent: The Lotos-Seat produces the best possible posture of the human spine-column for sitting for an extremely long time: The (here nearly maximal) supination of the hands leads to a retraction of the shoulders, an opening of the thorax to the front and through this to a physiologically correct position of the thoracic spine-column (kyphosis). The now correctly upright standing lumbar and thoracic parts of the spine column allow the neck spine column the best position and so for the head to be held fatigue-free with an elevated chin.

Before my mostly pronated hands had led to a pulling-forward of my shoulders with a tightening of my chest, which produced an unphysiological kink of the throracic spine-column, a "bump" (hyperkyphosis), much like the undesired "false kink" in a horse's neck, and stopped here the swinging-through of my spine's movements: no wonder, that my head often wandered downwards: it didn't have a proper support by the badly placed spine column! My stance became a falling forward of my upper body, producing more weight on the forehand. Additionally this spine-column stance led to a tilting backwards of my pelvis, producing an unintended collection of the horse with a shortening of the stride of the hind-legs.

The Gueriniere-seat produces the opposite: through the slight supination of the rein-fist and the mostly even more supinated switch-hand the rider's shoulders retract, opening his chest and putting upright in a physiological way every part of the spine-column: one can hold his head upright fatigue-freely! The pelvis is put upright in a neutral way, producing neither collection nor advancing.

Update 19.Okt.2016:

Advancing now in big strides: after many years of stumbling around on the forehand, evry week now there is pronounced advancement: if Paco has seemed to be reluctant to move forward and had to be driven forward with my constantly tapping legs, now he and Picasso nearly always move forwards much more easily and in fresher tempo, only occasionally a slight use of the switch is necessary, when the Pinky-Push should not suffice. (Because of this retracting seat Picasso notably had developed the habit to start every canter in sort of a Demi-Courbette, from which I always had to push him forward into a proper field-canter!).

Now everything learned in the past is easily integrated and, for me also unbelievable: I'm able now to canter Paco on a saddle-pad without stirrups or reins, only with switch-steering and supinated hands in the riding arena and on a circle canter calmly and evenly (hands-free, you could call it)!

For 10 days now I'm riding without spurs (for the first time ince 10 years!) and only now I notice, how much their use influenced negatively the rythm and the flowing movement of the horse.

To test the instruction of Eisenberg for reaching a shoulder-in now I've added a cavecon to the curb again. Eisenberg pulls the inside Cavecon-rein (with loose hanging curb-reins) and by this brings the horse's head to the inside, then he pushes the inside rein to the outside of the withers

(this way producing a "around itself bending rein"). If necessary, he uses the outside rein as a "from itself pushing away-rein", shoving neck and shoulders of the horse to the inside, if the seat aides alone are not sufficient. With supinated hands all this is astonishingly easy and precise to accomplish!

With 3:1 or 1:3 leading of the reins now the problem occurs that one has to decide: either to use the switch along the outside of the horse's neck, which makes the cavecon-rein on this side useless, or to use ths rein, which impairs the use of the switch.

The solution of this problem can be the use of the 4:0 or the 0:4 leading of the reins: with this the shoulder-in after Eisenberg is possible, too, and now the switch is fully operative additionally.

For straightening the horse in riding straight forwards cross-country a wonderfully supporting lesson!

25.10.16. Discovery of the day: Blockades of the Pinky-Push found:

In the rein-leading 1:3 or 3:1 it was recommended always to lead the single rein of the switch hand between 4.and 5. finger. Today it has occured to me, that this effects a retraction of the rider's belly, exactly the opposite of the desired result of the pinky-push! If you want to avoid this, you must let the single rein run around the 5.finger, too! ( I have mused for a while why in english-riding (with its mostly recommended holding upright of the rein-fists) no one ever had found out about the pinky-push: now we have the answer!).

The pinky push of the rein-hand also gets more difficult with 3 reins in hand: now one has to push forward pronouncedly the 4th finger, too, for a good effect.

26.Okt.16: Two more Pinky-Push-blockades found:

If you hold the switch (Fleck Dressage-Switch) like I always did before,

holding the lower olive within the fist, the Pinky-Push is severely impaired: one has to hold the switch at the shaft between the two olives.

Also holding the thumb pressed against the switch's shaft is contraproductive in the same degree: you may lay your thumb only on top of the cavecon-rein!

Result:

The switch wobbles a bit more in your hand, as you hold it like you would a bunch of flowers, but the advancing by applying the Pinky-Push now equally with both hands makes it more equal and more effective (although the switch approaches the rider's middle of his forehead somewhat more!).

Update 04. Nov.2016:

Among the Art-of-Riding depictions in

the stair-turret of Rosenborg castle (all shown in Bent Branderup's

"Royal Danois") we find at least three pictures with a pinky push of

the switch-hand:

Passetemps in the Terre-a-Terre,

Fanfaron in the Ballotade,

Pompeux in the Capriole.

The strongest, you could say the "Pinky Push Maximus" is used by his rider to effect the capriole of Pompeux. (Regrettably I'm still not advanced enough, to test it myself!).

So there probably is more than only a little bit of truth to Bent's assumption, that the danish horses of that time to no small part have been desired so much in all the world, because their riders could present them with this extraordinary brilliance!

5.11.16.: Insight of the Day:

Even Pluvinel held his switch nearly always in the "Bouqet-Grip" (as one would hold a bunch of flowers).

The opposite, the "Rod-Fisher's Grip" (thumb standing upright against the rod's shaft to stabilize the throwing-out of the fishing-line) we riders often use, too, for stabilizing the switch in our hand.

As I found out on Okt. 26. the rod fisher's grip blocks the Pinky Push massively. Today I noticed that one can increase the force of the Pinky Push considerably by righting up the thumb behind the switch and pressing the thumb against the switch (towards the rider) from behind!

After that I tried again the rod fisher's grip and found out, that pressing the thumb now against the switch to the front (away from the rider), tilts the rider's pelvis back (supporting collection).

So the Rosenborg depiction of the stallion Recompence suggests an initiation of collection in this moment, possibly starting a walk-passage.

Also the levade of the stallion Mars is supported bis the rod-fisher's grip.

No wonder, that Paco in the beginning of canter always elvated himself Demi-Courbett-like (once he even jumped a Vienna-style courbette with me) and Picasso, too, always started a canter with a Demi-Courbette: Not only had I been sittting heavily on the forehand by my pronated hands, I even pressed my thumb forcefully to the switch in the rod-fisher's grip!

Depicting the rod-fisher's grip in the "Royal Danois": Svan, Mars, Imperator, Tyrk, Recompence.

Pinky-Push

und Pinky-Pull: Biomechanical Relations

31.11.2016: Tips for Co-Researchers:

Those wanting to co-research the relations (the free I-Phone APP "Muskelapparat 3D Lite" is not bad) is better off understanding the following terms:

Abduktion: movement away from the body(-center),

Adduktion: movement towards the body(-center), as (in: Adverb)

antero-

: towards the front,

retro-: towards the back,

carpi: belonging to the hand.

To fully understand the possible movements in the information of the IPhone-App one has to undertand the Neutral-Zero-Method (engl.Range of motion (or ROM)).

The Neutral-Zero-Method is used internationally to document impairments of joint moveability and describe them in degrees; the name refers to the reference model in which every joint has 0°.

Every deviation is noticed in plus- oder minus-degree numbers.

If you look at the wikipedia picture, you will notice that the hands are depicted in full supination, despite the normal position is "along the trouser's seam". This unnatural reference-position is necessary to give the carpal-joint-movements an abduction and adduction.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neutral-Null-Methode

(For the upright standing fist in the Gueriniere-Seat (basic position) the correct NN-description would be "-90° supination" or, seen from the other side, "+90° pronation").

For us it it is much better to refer not to the NN-Refernce position, but to the normal position, which is the upright standing fist, from which a pronation of max. 90° to one side and a supination of max. 90° to the other sides are possibble, thus eliminating the use of minus degrees..

Example 1, rein-leading one-handed left: in riding a straight Straight without accelerating (rider's pelvis in mid-posture) the (left) rein-fist will be held in a supination of 10°, the (right) switch-hand in a supination of, say, 50°.

Example 2, rein-leading one-handed left: for advancing while riding a straight Straight with Pinky Push (rider's pelvis in forward tilt) both hands have to be held in 0° .

Example 3, rein-leading one-handed left: for turning the horse to the left, the rein-fist will attain for a few seconds a pronation of 80°.

At the moment I suspect the following relationships: the Pinky-Push is started by a radial kinking in the carpal joint (abduction of the hand) through the tightening of the radial hand-bending muscle and the radial hand-extension muscle (musculus

flexor carpi radialis und musculus extensor carpi radialis).

The desired masive conduction is reched by a strong tightening of their opponents: the ulnar hand-bending muscle and the ulnar hand-extension muscle (musculus flexor carpi

ulnaris und musculus extensor carpi ulnaris).

Through this reflectively a tensioning of the long head of the Triceps-muscle (M.triceps brachii) occurs, which leads to a forward-downward movement of the lower rim of the shoulderblade, which pushes ribcage and thoracic spine to the front.

The result is a flattening of the thoracic-spine's curve (>hypokyphosis), this in turn to a prounouncing of the rider's lumbar curve ( >hyperlordosis). This movement effects a tilting forward of the rider's pelvis which leads to an advancing of the horse.

(It is still unclear to me, if the m.subscapularis is involved or how the other relationships are.)

The Pinky-Pull, the opposite movement with leading backwards the little finger to initiate the collection would lead then over the flattening the lumbar spine to the tilting back of the rider's pelvis. The reason for it's weaker impact might be that a retreating of the shoulder-blade produces much less force than a pushing forward into the ribs....

Update

22.12.16 and 04.02.17:

After successfully testing Eisenberg's way of inducing a shoulder-in and including it sometimes in my aids repertoire, I tried next his way of croupe-in with an 80° angle to the wall: disappointingly this was not possible in a soft way and I had to give up this stressful project after 2 days.

Reading up afterwards in Gueriniere's text, I found his sharp rebuke of this method, criticizing hereby also very good riders as Pluvinel, Newcastle(S.234), Eisenberg (S.38) and

Ridinger! So even for these grandes of the art of riding sometimes we have to realize: "Nobody is perfect!". (See also Branderup/Kern p.73 [where this critique is interpreted only regarding the counter-shoulder-in = shoulder-out]).

I was lucky, that I (in reality more my horses) had recognized very early on, how dangerous and harmful this lesson might become!

Since then I'm using mostly the croupe-out and have begun to use Gueriniere's much stronger "croupe-au-mure", which he calls a leg-yielding with the horses's head bent into the direction of movement, with an 80° angle to the wall. In the longer, younger Picasso this is produced more or less easily, but with the older, shorter, strong backed Paco it's considerably harder to achieve and maintain!

This "angle to the wall we are moving along" could also be expressed as "the angle to the wall we are moving towards", which is 10°. This 10°-angle appears everywhere with Guerieniere: he uses it in the Traversale, in the Karree, the Demi-Volte and the Pirouette, too.

The most important sign for a successful, healthy croup-au-mure, besides the maintaining of the ever steady angle to the wall, is a beautiful arc of the outer front leg over the inner one, as this shows it is not on the shoulders.

Under no circumstances the inner front-leg should be permitted executing a wide, spectacular lunge step, as this brings the horse onto its shoulders and additionally often leads to a falling out of the hind, and thus to a falling apart of the horse. By this all the three most important goals of this lesson are missed: The higher erection of the forehand, the increased treading under of the hind legs and the preparation for a canter sideways in the same posture and angle.

After only 10 times I got the impression of a real improvement of the shoulder's lightness.

Croupe-in along the wall I'm using only rarely now, and if, only with a distance of at least 1.5m to the wall, as de la Broue and Gueriniere just find acceptable (and only for exceptional horses).

Update 08.01.2017:

If the rider carries the Fleck Dressur Switch between the olives, a far too long protrusion of its end results; Gueriniere recommends the vanishing of the switch's end within the fist anyway.

After changing to a natural switch today I noticed a possible blocking of the Pinky Push, which occurs when the switch ends centrally in the palm. If one wants to use the Pinky Push, the switch's end has to rest on the ground phalanx of the little finger!

28.Jan.2016: 400 years old confirmation discovered:

While browsing the La Broue today I discovered that he (apparently as the only one of the old masters) described a direct correlation between a drawn-in belly and rolled in shoulders: the seat should be:

"pushing the belly a bit forwards to avoid a vaulting of the shoulders" ("L'estomac un peu avancé pour ne paroistre avoir les epaules voultees").

Update 05.02.17:

Meanwhile it's become clear to me, that the reason for supinating the switch hand is not only to let the rider's belly come forward a little: a profit occurs also through the neutralisation of the switch hand's thumb despite it is lying upright at the switches shaft,same as in the rod-fisher's grip: as in a supinated hand it can only press sideways, which doesn't have any effect on the position of the rider's belly. So nothing happens, if the rider gets rigid and presses his thumb against the switch!

The older

people get, the more often a rounded back occurs. This means a

hyperkyphosis (a rounded hump) of the upper part of the thoracic

spine has formed . This spine deformation leads to a bending forward

of the shoulders which are permanently rolled in and held forward, and thus producing more or less fixedly pulled up shoulder blades.

In this case

the pinky-push doesn't come through or if, then only in a diminished

way: so the rider must try actively to push his belly forward for

tilting his pelvis forward, if he wants to accelerate his horse.

Additionally he can hold his upper body somewhat backwards, to

minimize somewhat the falling forward tendency of his head.

Holding his

legs „before the horse“ seems to be equally important, too.

Though

supinating his hands in this case doesn't bring a maximal effect,

too, nevertheless a little and palpable effect occurs.

Every human constantly has to take care of his body posture and to correct himself at

least 50 times a day: in sitting, walking, lying, at the desk, at the

computer (vertical-mouse), driving a car,etc.

The German

chancellor knows this, too: her Merkel-rhombus doesn't only give her

a good standing, but is a little therapy, too.There are

many websites showing very good exercises of Yoga, physiotherapy and

breathing techniques to be found on the net.As two

thirds of the patients don't feel pain through many year's, the suffering

is not great: maybe the wish for a good rider's seat might here

work like a forehand-erecting curb?

Update

19.02.17:

Not only the nearly maximal supination of the switch-hand is neutralizing the

pressing-thumb: the same importance has a strong extension of the

index-finger along the switch-shaft : So I assume that

the extensor- or the flexing-tendon of the index finger blocks the upper-arm muscle, which pulls the lower

rim of the shoulder-blade backward (leading to a tilting back of the

rider's pelvis).

Knowing

this, the rider gets an exquisite additional incentive to observe the

correct holding of the hand.

In my case

the croupe-au-mure to the left in the left-hander seat is especially

hard: as most will do, I trained the Gueriniere-seat first in the

right-hander seat, and only after some months in the left-hander

seat, too, so the latter always remains a little weaker.

On top of

that, Picasso's worse bending side is his left.

So here my

seat is falling apart most easily and I get rigid which often causes

the horse to go backwards in the croupe-au-mure. Here a

pressing-thumb would disturb massively! Noticing this now, I will

put the switch-hand so low that the experimentally sideways pressing

of the thumb to the switch creates not the slightest

muscle-tensioning in my back: then I will be able to correct the horse

significantly better: a palpable lightening occurs!

Holding the switch-hand (now left) a fist's height lower and hooking in

the left curb-rein to the little finger it acts now with a previously

unknown lightness and precision and I'm able to lead this rein in the

same easy, slightly hanging-through way as in riding one-handedly.

The same

applies to the training of the 80°-sideways (see my commentary to Saunier

on Fundstücke/Finds) on the carree on one hoof-beat at the

turnarounds on the haunches in the corners, or at the demi-volte in

the carree (volte inside the volte).

Update

02.03.17:

New terms necessary!

If the rider uses a non-symmetrical seat and also intermittently wants to change the way of seating, the terms "right" and "left" loose their definite meaning, at least if one doesn't want always have to add: "in the left-hander seat" or "in the right-hander seat".

Therefore now I am using the following definite terms:

-

the "switch-hand" or " the "rein-hand";

-

for the direction of riding in a manege: "riding on the rein-hand" / "riding on the switch-hand";

-

for the reins: „switch-hand-rein" (also: "switch-rein") / "rein-hand-rein";

-

for the type of bending: "bent to the switch-hand" (with the switch held crosswise over the mane) / "bent to the rein-hand", also: "bent away from the switch-hand", both with the switch parallel to the horse's neck.

Saunier's hand-positioning deviates a little from Gueriniere's, the description thus would be:

Interim-Report

02.March 2017:

One

year has gone by now, since I began to make the first tentative steps

in the direction of the Gueriniere-Seat: it has fascinated me

increasingly and I have succeeded in finding out the following:

-

My

initial goal of always holding theright arm lower has not proved

to be good: though in the switch-hand bending it helps much, in the

rein-hand bending and in riding straight it is a hindrance for horse

and rider: and so in the latter cases the hand tends to move upwards

anyway. But for my researching the impact of supination, it was an

invaluable tool for teaching myself!

-

The

goal: Hands never in pronation has proved to be very effective,

though I soon had to concede to one exception: if you want to turn

the horse to the rein-side, you have to pronate the rein-hand distinctly, so that the thumb points to the outside.

-

The

goal “The thumb always points straight ahead” has proved very

valuable,too( a small deviation of ar. 20° tin the direction of the

switch-hand seems not to harm its effect).

-

My

discovery of the Pinky-Push during this research year is my greatest

pride and had been possible only by the change from pronation to

supination. I see it as a big step forwards and hope to abolish my

use of spurs completely ( or at least to only 10%), just as the old

proverb, cited by Newcastle, says:”A free horse doesn't need

spurs!”

-

The

third column of my Gueriniere-Seat should be the always held

forwards legs. This was very difficult at the beginning, but got,

after polishing the use of the Pinky-Push, easier and easier. The terming: “Legs at most times held

before the horse”, having been a mis-translation originally during my agonizingly slow word-by-word translation of Broue's, I will keep it unchanged nevertheless, as it very clearly expresses my seat-feeling. By this

position of my legs the effect of my seat and my body-posture have

improved considerably.

-

Since

finding out the effect of the pressing-thumb, I have worked for a

long time mainly on preventing the unintended collection by it. With

stretching the forefinger along the switch-shaft this gets fairly

easy now and in the last days I have even begun to apply it again sometimes.

Update

14.03.17: The "protruding lower neck" as a sign of quality with

Gueriniere

Through my work in the Croupe-au-mure I became suspicious of his many depictions with a so-called "protruding lower-neck". Up to today I had believed this to be a sure sign of a pushed-down back of the horse. We all know the pictures of horses with highly elevated forelegs and a dragging hind, the latter causing a tilting upwards of the horse's pelvis and with this a shoving back-out of the hind-legs, a lengthening of the horse producing a pushed-down back and kissing spines. Only: with Gueriniere to the contrary the hindlegs are pushed forwards under the horse, the pelvis tilts down and so a vaulted-upwards back is produced: by this no pushed-down back should be able to occur!

Here the ocurring visibility of the lower neck by taking backwards the upper neck with the horse's head means that the forehand is maximally erected, and the weight of the forehand is pushed to the hindlegs as much as possible: the forehand becomes free (of weight) and by this can move much more freely!

Seen in this light the depictions on my Finds-Page , it becomes clear, that a slightly visible lower neck was proudly shown on the best horses of their times.

Update 22.03.

During the last week my horses have corrected me by actually showing a sinking of their back as a result of a too far retracted neck and head: so I have to shrink the usefulness of my gradient of collection to a much shorter range.

Should I find a suitable PC Software showing the weight on each hoof and processing my gradient of collection in real-time, I hope to find out the exact borders of "Anti-Collection" (with shoving back of the hindlegs and the striving away of forelegs and hindlegs from each other, on one hand, and on the other the exact point of pushing back the upper-neck of the horse too far. Until then I can rely only of the feeling in my seat again, hopefully telling me in time if one or the other occurs.

Maximally well erected forehand with a visible lower neck:

My impression is, that the old masters took back the upper neck only to the line perpendicular to the axis of the horse's body, and thought only of more than this as harmful. So a visible lower neck should be judged a mistake only, if the upper neck is retracted behind this perpendicular line.

The definition of this Angle of Up-Straightness then would be: Angle of the frontal rim of the neck to the body's longitudinal axis.

pushed-down back:

In the sketch by Pablo Picasso a pushed down back is produced through "Anti-Collection", wherein fore- and hindlegs are striving apart: a sinking back is the result, with a much reduced bearing-ability.

Too far retracted upper-neck:

With the Lecomte Hippolyt and in the east-indian school-halt we can see the second type of mistake in collection: the upper neck is retracted too much.

Gradient of Collection

The

angle of Up-Straightness alone doesn't say everything about the

degree of collection, we have to include the effect of increased

load-bearing of the hind-legs, too.

In

the standing, highly collected horse we can see very well, and even

measure to a little extent, what is most important to

La Broue,Newcastle, Gueriniere and Saunier; from this I have developed

my “Gradient of Collection”: If we draw a straight line

from the highest point of the horse's neck (the atlantoaxial joint)

to the farthest back standing leg (which is bearing the highest

load), this line is the steeper, the nearer these points are to each

other. This gradient (= steepness or tilting angle) is variant due

the different shapes of horses: the type of frame, the length and

form of the neck, the degree and way of the bending of the haunches,

but also due to the lesson: School-Halt or Courbette (Levade) in

standing, Piaffe, Walk-Passage, Trot-Passage etc. in movement, and is only

applicable if a.) there is no anti-collection and b.) the angle of

Up-Straightness doesn't exceed 90°.

In

the School-Halt we can see very well how the freeing of the shoulders

(of weight) increases with the steepness of the gradient of

collection: in the bent School-Halt at first only one shoulder gets

completely free of weight and lifts up first, and only when the

complete weight of the horse is fully on the hind-legs, the second

foreleg lifts up, too.

Measured

Values: Most of the horses on

my Finds-Page are standing in the square type, so in the following I

won't indicate the type of frame. All values can only be

approximations, as many horses are depicted somewhat obliquely!

The

Grecian school-halt statue shows a gradient of collection of 70°,

The

Saracen from the neapolitan. crib: 69°,

Roman

seal-staone: 65°

Etude

pour la course des Barberi: to the forward hind-leg, which ids the

loaded

one: 72°

Vendome:

68°

Riding

lady in the Bois de Bologne: 62° (here the weight of the rider lies

more

backwards, due to the

side-saddle)

The

mesopotamian school-halt:: 58°,

Napoleon

on the white horse: 59°

School-halt

in the Parthenon-Freeze: 70°

Broue,Newcastle,

Gueriniere and Saunier use a high angle of Up-Straightness and a

steep gradient of collection for many lessons: in the shoulder-in,

croupe-au-mure, the Traversale in Passege (and Passage?) and in the

Demi-Volte and Pirouette.

Maybe

one day we will find out that a definite gradient of collection is

the best one for the fatigue-free skipping in courbettes ?

Ideal Levade/ then Pesade with Gueriniere,

(the head-turn of the rider is depicted wrongly: artistic freedom of the painter)

Update

12.April 2017

Yesterday

I found in La Broue's "Cavalerice" that it is necessary for a good

85°-sideways movement, to not bend body and neck of the horse! Now this

cleared up Saunier's words regarding the holding lower of the inside

hand: by this he achieves positioning the horse's head without executing

an "around-itself-bending inside rein"!

Gueriniere, too, writes that body and shoulders have to be straight in the 85°-sideways movement!

Thus I have possibly solved the riddle about Guerinere's hand positioning completely:

1. He

puts the switch-hand lower, to minimize the effect of the inside rein

on the horse's neck, to prevent a neck-bending (with the inside rein of the snafflecurb) while positioning the

head to the side he is moving to.

2. He supinates the hand to achieve an upright and free rider's- seat.

3.He extends his index-finger along the switch-shaft to avoid using a pressing-thumb inadvertently.

Update

16.April 2017:

Having

trained the 80°-sideways-walk over four months now in the

Croupe-au-mure (for which Gueriniere demands, to put the horse's outside shoulder onto one line with its inside hip), the Renvers-Karree (with ¼ pirouettes on the forehand

in the corners) and the normal Karree (with the croupe to the centre

and ¼ pirouettes on the hindlegs in the corners) and after some

tries to hold this angle in the sideways-canter in the field, I've

succeeded today for the first time in closing the Demi-Volte, which I

had started in the Sideways-Walk, by two jumps of

Terre-a-Terre while performing a Trot-Passade. Broue calls this

sideways-canter at the end of a Demi-Volte „Terre-a-Terre“; (see

Vol. 2, p.43).

Newcastle sees the diagonalized

walk as a result of the sideways-walk (with

him for example with the croupe towards the pilar, which he calls

"half a shoulder forward"). He

writes, that when the forelegs are crossing, the inner

hindleg moves to the side, and when the hindlegs are crossing,

the inner foreleg moves to the side, so this is the action of a

trot.(= two-beated)

Also

about the Sideways-Walk, that when the forelegs are crossing over, the

forehand gets narrow and at the same time the hind gets large, as the

inner hindleg moves to the side. At the next movement, when the

hindlegs are crossing over, the hind gets narrow and the forehand

large, as the inner fore-leg moves to the side.

So

in the Sideways-Walk the horse is always in half a Terre-a-Terre: the

Terre-a-Terre of the hindlegs, when thess are large, and in the next

moment in the Terre-a-Terre of the forehand, when the latter is

large.

Update

23.04.2017:

Wanting to ride a traversale in walk yesterday, my horse took it for granted to start going sideways: I was very astonished! But no wonder, after all this months of work in the Sideways-Walk! So I had to tell him explicitly how much forward I wanted him to produce. At this point it became clear to me how wrong I had been over all the years in my thinking about producing a traversale in working-trot.

The explanations of Gueriniere in the chapter:„Passage“ are also (possibly mainly?!) meant for the walk-passage as here again he writes: "As we have said in the chapter "artidfical gaits" the Passage is a restrained, measured and cadenced Walk or Trot, wherein the horse lifts up a foreleg and a hindleg crosswise at the same moment, as in the normal trot, but much more shortened, determined and cadenced as the ordinary trot, and with every pace it is doing, the hoof in the air not more than one foot (ab.30cm) moves foward than the hoof still on the ground.“

Very difficult is to rethink the traversale from the space-expansive (on the forehand) one used today, to a slow Walk-Passage-traversale with erecting the forehand highly!

When Gueriniere at the changement through the manege on two hoof-beats speaks about Broue saying, that the rider needs to be very careful in supporting the crossing outer foreleg in a certain moment, I'm reminded now of the way, I'm trying to support my horse during the 80°-sideways.

At the moment I prefer to execute a steep, but shorter sideways-walk-traversale, as I'm still much to impatient for a long and slow changement.

Update

29.04.17:

Since finding Saunier's term „Walk-Passage“ I have suspected, that the passage, which in some old texts was reserved for kings and high nobles, often meant a walk-passage and not a floating-trot. Now I have found a text confirming this: in the chapter "About passegeing straight-forward and where and when", where Nicolas di Santa-Paulina (1696) writes in the L'Arte de cavallo, S.96:

"There are four ways to passage a horse:

The trot-pasage is suitable for young and for bizarre riders [...].

To passege in walk means that the horse elevates his foreleg and hindleg as in the trot, but not in the exactly very moment as in the trot, merely with a not perceivable pause before moving the other leg; the horse lifts the forelegs higher than the hindlegs, and when the horse lifts the legs equally high on both sides, it is called a Passegio, which, despite not being as gracefully as in the trot, is majestic nevertheless and appropriate for a prince."

So the walk-passage straight-forwards was a dignified, calm way to present themselves for noble and powerful persons, too.

Update 21.May 2017:

Having achieved some nice Terre-a-Terre jumps at the hand some days ago, Paco today, after an accidently triggered Terre-a-Terre jump backwards during the Croupe-au-mure at the hand, let himself stopped during the next one so far, that he had only set his hindlegs far under his belly, but didn't let his forelegs leave the ground: so he stood in a posture with a very much lowered croupe, and succeded even in taking 2 steps sideways in this posture; maybe this will be my way to achieve a good gradient of collection during the sideways?

My training program (in the arena) always starts with a school-halt at the hand, continuing à la

Gueriniere (though at first in handwork): shoulder-in (35°) in walk on both hands, then croupe-au-mure (80°) in walk on both hands, then mounting the horse and in a fresh trot straithening him on the middle line through the length of the arena, then from the saddle shoulder-in and croupe-au-mure in walk again.

For the 80°-sideways I place the switch same as in the woodcut in the Sébillet: obliquely forwards down before the inner shoulder (at the ground I lead the horse from the outside).

Update 07.Juni 17:

Meanwhile is has become clear to me, that in the Gueriniere-seat I don't only have my legs before the horse (sometimes only a little bit, but always palpable!), but also my belly, and, because my upper body is not tilted foward anymore, this part also is carried before the horse's movement: the rider feels carried like a ship before the wind! Now I call it: The rider is sitting before the horse.

Looking back now my old seat had the feel of pushing a wheel-barrow: the rider's legs and belly behind, the upper body fowards und the rider's head forward down.

Update 07. Juli 2017:

Whilst researching the pulling-up of the

rider's heels, another important benefit of the "legs before the

horse" became clear to me: testing, after many months, once more

the wrong pulling up of the heels during the "legs behind the

horse" I got reminded, that the rider sometimes gets hit against the front part/the gallery of the saddle; long had I forgotten

this uncomfortable side effect of the customary seat!

Update

24.July 2017

After the last supervisory lesson by Marius it became clearer to me that

Guerinieres invention of the term „Croupe-au-mure“ is wonderfully suited to prevent riding the sideways with the head to the wall, but as the wall is very long, the rider tends to do it far too long far too early. Better might be de la Broue's approach: at first only one or two paces sideways, still combined with a little forwards, then four or five paces straight forwards, increasing this only incrementally over weeks.

Because this training starts traversale-like, it is easier to think (as in a traversale we are always supposed to do) of the desired 85°-angle to the wall along which one moves along (here the short side of the riding arena) as a 5°-angle to the wall the horse is moving towards (here the right side).

Update 12.Aug. 2017:

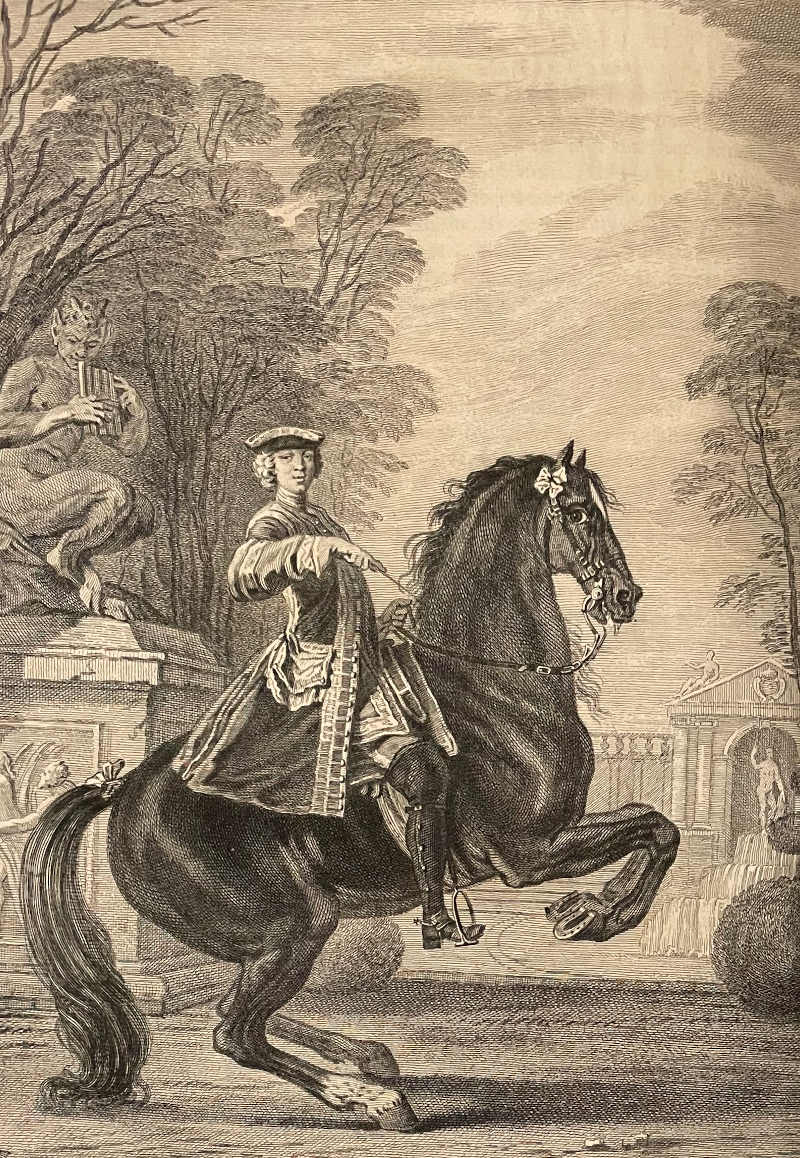

During my holidays I had ample time to think about Nestier's school-halt in it's wonderful easy manner and to analyze the aids he is giving.

He uses the

Gueriniere-seat: the rein-hand standing upright with the thumb

pointing forwards (assumingly the hand is supinated slightly ab.

10°); the switch ends within the rider's palm.

The rider holds

his legs before the horse.

To produce the

school-halt he pulls his shoulder-blades even more together and more

downwards, by this the rider's breastbone advances forwards

significantly; the horse's mid-back

is somewhat relieved by slightly raising the rider's heels and, additionally,the upper thorax of the horse

gets unburdened by a stirrup-tread on both sides because now the

rider's thighs gets wider.

He exerts a

slight pinky-pull with the rein-hand which leads to a backwards tilt

of the rider's pelvis. So the rider's back comes to be a mirror of

the horse's back: Erection of the forehand coupled with a tilted

pelvis.

In this picture

he presents a special, very complicated situation for the support of

the right-bending in a not very far educated horse: leading the right

curb-rein with the right hand in a lower position, just as Gueriniere

described 20 years earlier in his “Ecole de cavalerie”. (A rider

with only some years of academic training better should use the

left-hander seat if having problems with the right-bending!).

The curb with a

very short lower branch makes the rein-action even more difficult, as

with this even a small rein-displacement leads to an impact.

Deviating from

Gueriniere's depictions he holds the switch downwards (in the

ski-stick position) and leads the right curb-rein between ring- and

middle finger. The switch lies fast at the right thigh, to prevent as

much pronation of the switch hand as possible and to give the hand as

much freedom of movement over the switch's end. Holding the hand

this way makes the right-bending even more difficult to achieve, as

the rider cannot try inducing the horse to it by laying the switch

parallel to the left side of the horse's neck.

The rope, which

serves as a second pair of reins is not used at the moment; its inserting point is too high for a normal bridoon: if it is a nowadays unknown bridling stays unclear still.

The chainette at the ends of the lower branches indicate a snafflecurb.

With kind permission of the British Museum

Update

01.Nov.2017:

The stable Gueriniere-seat enables the following very fine and light giving of aids to bend the horse:

Holding the switch in the upright fist in the semi-bouquet grasp (the end of the switch vanishes completely within the upright standing fist) with a foward tilt of the switches tip of only 10°, while supporting it in the palm, one can by bending and hyperextension in the carpal joint induce finely calibrated a bending of the horse.

At the start, to sensitize his body and that of the horse, one begins with the strongest bending and extending in the carpal joint: for bending the horse to the switch-hand side one uses a hyper-extension and holds the switch-hand behind the rein-hand. For example, to get a shoulder-in to the right, being in the right-hander seat, the fist is rotated so far out that a maximum of hyperextension results: the knuckles (MCP-joints) of the switch-fist point as far to the right as possible, the switch-hand stands farther back than the rein-hand, and the rider allows his left thigh to press a little more against the left forward part of the saddle. With this the left shoulder comes a little forward.

Wishing to change into a right croupe-in, the rider simply needs to take his left shoulder a little back and lift the left thigh somewhat from the left side of the saddle, which leads to a turning of the horse under him into the croupe-in.

For the bending to the left (the rein-hand side) he shoves the switch-fist farther forward than the rein-fist, turns it from hyper-extension into a strong bending, so that the knuckles of the switch-fist now point to the left side, and allows again additionally a little more pressing of the right thigh against the forward part of the saddle for the shoulder-in; for the croup-in to the left he again turns the horse under himself.

Also a very smooth change from shoulder-in right to croupe-in left is finely possible .

Training is done best on a long straight way outside, or in a big riding hall on the middle line (because only here the pressure produced by both walls are equally strong on the horse)

Naturally the same applies for the left-hander seat, inversely.

After achieving the feeling for this aid, and some routine, you will recognize that for the most time there will be no need for a strong rotation in the switch-hand's carpal joint, which can even be far too strong during canter, where the horse can easily feel overstarined by this light aid and begins to throw his head oder actually stops the canter! Here one is learning speedily, how little is needed to hold the horse in shoulder-in or croupe-in while cantering!

A straight Straight between these aids, exerted minimally, is achievable more easily!

Update 25.Nov.17:

Having translated the Chapter 33, Vol. II accurately

now, in preparation for my La Broue book, I'm training the full halt

from a lively gait after his fashion: but customized in the way, that

I use the school halt instead of going backwards (as the horse is

not able or willing to decide reliably which one I want, and will

prefer to go backwards, because this is much easier). I would never

have expected, that this heavy type of halt would leave the horse so

calm: but the 4-5 steps in a very collected walk , which thanks to the sideways

training gets more and more unhurried and relaxed, and the 2-3 turns afterwards are pacifying the horse

completely, and nevertheless it shoots forwards promptly in the next

try. Already this lesson seems to improve all the other lessons, as he wrote, and the horses get more assured and courageous every time.

L'Arrêt avec le Cavesson (The full halt with the cavesson), Lithographie by Charles Motte, ar. 1830, after Eisenberg

„To form the full

halt with grace, the horse must bend its haunches, it shall not

traverse and not press against the hand, it shall hold its head still,

the neckline high and before the rider. With young horses one is not

allowed to make the full halt too short or to suddenly, so as not to

ruin his hocks or his mouth. At the inducing the rider has to approach

his calves to the horse to animate it, he brings his body back, brings

the hands with the cavesson and the reins higher, and after that extends

his knees vigorously and steps into the stirrups and at the same time

lowers the switch ."

30.11.2017

During the translation of Chapter I-34, immediately I thought of this picture from Delft: this rider might have been influenced by the Cavalerice, holding the hind legs of his horse wide apart.

Tile from Delft, around 1650, the Rider is hollding his legs before the horse

18.12.2017: Positioning the rider's legs: Interim report after 21 months

The art-rider's seat I had named after Gueriniere, because I found in his book very clear pictures which regrettably cannot be found in Grisone's and La Broue's; because I feel Pluvinel's seat not correct and Newcastle's to far in front of the saddle.

The expression "Legs before the horse" fell into my lap by a translation accident und is used by me nevertheless since then because it hits the mark correctly.

If he holds his legs before the horse the rider can feel the power he is treading into the stirrup travelling through the whole length of his legs straight into his complete spine, without losing his seat, not even when he pulls up his heels. The musculus gastrocnemius (the dorsal thick belly of the calf muscle, which while lifting the heel would lead to an additional bending in the knee joint) is then little or complettely not in use. but more or only the flat calf muscle musculus soleus: the rider often gets the feeling of a tightening only of the calf's sides.

Are the legs but behind the horse, this line of force will be broken at the rider's knees and then the lower legs become merely appendixes of the knee joints: the rider looses stability significantly in the longitudinal direction of the horse, but also sideways stability, falls forward and often hits the forepart of the saddle unpleasantly: here the dorsal thicker part of the calf muscle, which is used to drive the horse forwards, is tensioned more.

Delft Tile, ar. 1790, the rider has his legs far behind the horse

A middle postition I couldn't find out yet, it seems there is only before or behind the horse. So my aim is always to as soon as possible return to holding my legs before the horse again after having them put back for a short time, be it out of old habit or for using them more behind as an aid.

The line of force can also get broken completely through bringing the legs far forwards, as in "legs over the horse" [see Marc Aurel or the mesopotamien school-halt]; here also the lower legs thighs are merely appendixes of the knee, additionally now the feet have no or only very little contact with the stirrup plates. Here no muscle on the calf's back is tensioned. (Riding completely without stirrups, naturally there is no build-up of this line of force possible: one either lets his legs hang downwards straightly or puts them over the horse).

Holding the legs before the horse, the rider always treads a little bit into the stirrups and uses a force between 20grams and many kilograms, depending on the need.

Here develops a far increased fundament for the rider's equilibrium than that of the englisch seat, one could call it a tripod by bottom and both feet: the rider stands and sits simultaneously like on a one-legged standing-stool.

A very important benefit is that the rider can dampen very finely the shocks, which the horse's back gets by the rider's weight, depending on the degree of tension in the flat calf muscle (m.soleus).

The distribution of the rider's weight I guess is: ar. 60% on his bottom, 15% each on every thigh and ar. only 1% to 5% on every stirrup plate (except during a stirrup tread).

But in the stirrup tread there can arise sometimes a load of ar. 50kg on this plate (as my horse have a wide fundament, the don't sway hereby).

The difficult situation regarding trhe equilibrium in the englisch-seat costs the rider much of his concentration, whereas in the Gueriniere seat a lot of this gets freed: the rider can put it to work on other tasks (in the first days actually something seems to be amiss!)

What the old masters told us:

Grisone 1550: The rider shall let his lower legs hang down in the way, that they position themselves on their own in the stirrups, as if one would be standing on the ground; the points of the feet turned so, that at turning the horse on the resp. side they point into the same direction as the rider's nose.

La Broue 1593: The back straight and firm, the thighs fast at the saddle like glued on. The kness closed and turned more inwards than outwards. The lower legs as near by the horse as necessary, firm and straight, as in standing upright on his legs on the ground, if the rider has a big or medium stature; if he has a small stature he shall, when possible, hold his lower legs forwards adjacent to the horse's shoulders.

The heels lower than the points, neither turned inwards nor outwards [means ar. 30° outwards rotated as in normal standing], the soles of the shoes shall lie straight and with safe dependence upon the stirrup plates and so, that the point of the shoes surmount about one thumb's breadth the plate.

Pluvinel 1626: The rider has to keep himself upright in the saddle as in standing on the ground, the lower legs far forwards und shall be treading fast into the stirrups, holdings his knees closed always and with all his might. With the point of the feet coming near the horse's bow, his heels pushing downwards; his soles shall be visible from the ground. Picture from: "Le Manege Royal":

Newcastle (frz.1.Buch) 1657: The rider shall sit in the front of the the saddle as far as possible, letting his legs hang down as if standing on the ground, thighs and knees as glued to the saddle, the legs put firmly into th stirrups, the heels somwhat lower than the points.

Gueriniere 1733: Holding the lower legs unconstrainedly straight downwards, not too far forwards, because one has to use them sometimes behind, but not too far behind, because one would come with his aids into the flancs, which are too ticklish and sensitive to work there with the spurs. The heels not too deep down, to prevent the lower leg from getting stiff, the points of the feet turned not too far outwards, for the spurs not to touch the belly, and not too far inwards, to prevent the paralyzing of the lower leg. But rather one has not to rotate the lower legs inwards, but the thighs. In his book also these pictures can be found:

Prizelius (1777) shows on nearly all his depictions a wrist-flexion of the minimally supinated switch hand, together with the "legs before the horse":

Looking at the old pictures one realizes that the advice to let hang down his legs straightly can be meant in two different ways: a contemporary show-rider, grown up in the englisch seat, with his legs behind the horse, wants to say: so that still at least a little angle in the knee joint occurs, with tightening of the thick m.gastrocnemius ( = "not treading into the stirrup!"); and on the other hand the art-rider before 1800, who is holding his legs just a bit before the horse, without an angle in the knee joints, ( = "always at least a minimal tread into the stirrup!"), except for short aides.

While holding the legs before the horse at the beginning is quite difficult for the rider to uphold, for the horse it is even harder: during riding english the relaxation of the rider is signalled to the horse by throwing away all pressure in the rider's seat and body, sometimes relaxing the legs by putting them fowards, meaning pause for the horse, but now the real, loose work shall start with exactly these signals!

The horse has to adapt greatly, as the rider tries to hold his legs forward as often and as long as possible, by which from him are stolen not only the spurs (Pluvinel) but also the calfs and the heels for driving the horse!

Here he must find other means and learn to use them: at first one thinks of the switch, but it alone often will not suffice: he also has to dismiss the sitting on the forehand, which is used in the Englisch-/race-/jump-/hunting seat, in favour of a forehand-unloading seat, which consequently will be a hindquarter-loading seat, which is an important gaol of the academic art of riding, by bringing back his upper body a little, by not pronating his hands, by letting his belly come forwards slighthly, by not rollig in his shoulders, and so on.

Additionally he has to allow the horse to step forwards freely by tilting his pelvis forwards (or at least not letting it stay tilted backwards) and, if appropriate, use the pinky-push; and instead of driving the horse by heels/calfs/spurs using a stronger or weaker loading of the stirrup at the time when the horse rotates downwards its ribcage on the same side, to increase the forward stepping of the hindlegs.

Increasingly in the lessons known to him and the horse, the clutching of the lower legs behind the horse will vanish, but in a new lesson easily occur again, which is not always to be seen as a mistake, as the horse can agree only to a lesson it understands, and the rider also has to get a feel for the new lesson, which all can be achieved often only by increased driving with the legs. Thes "false" aides can be abandoned or at least reduced in the later training.

Update 23.12.17:

The horse-scales have been here: Paco's weight combined with mine and saddle is 660kg. Only the forehand on the scales it shows 330kg, the scales is 20cm higher than the surrounding ground where Paco's hindlegs are standing: that means some weight is already shifted to the hind already. We had only very little time and could only use our standard school-halt once: the scales showed then only 240 kg for the forehand: 90kg less on the forehand means 90kg more on the hindlegs = 420/240kg. Described in another way: the forehand was unloaded from normally about 60% to 36% of the weight! So in this medium school-halt the haunches had instead of normally ar. 40% now 64%: a real, slight "arret sur les hanches"!

Update 19.01.18

To train once in a while a whole halt on the haunches from the lively trot or from the canter produces actually the effect La Broue predicted: all collecting and higher lessons get much better, from the school halt and the very collected trot onwards!

Since having begun very cautiously to test his instructions for the Courbettes, I have begun again, after many years, to levade my horses, which I avoided for a long time out of fear to produce a harmful Pesade: As La Broue describes, we should begin with Levades out of the forward movement. With me, it developed into somewhat else, so at the moment I can elevate the forehand of my horses somewhat during a slow canter uphill at every second leap (my inner picture for this is the tile from Delft of 1650, which may show exactly this movement, and Ridinger's pictures "A strong halt out of the canter" or "The relevated canter").

While doing this, I think of La Broue's comparison with the "Jeu de paulme" and the result is a body stance of the rider similar to the forearm pass in volleyball: the rider's legs then are so far forward and a little bit up, that one has to speak of the "legs above the horse" here, all the more as the rider's knees are bent a little bit, too; additionally the rider's hands come forward, too. On top of that, I reinforce the lifting of the horse's fore-hand by a pronounced pinky-push, and for now I achieve (perceivedly) sometimes a distinct elevating of the forehand. This elevating of the forehand leads to a distribution of much more weight to the hind-legs, which then bear the weight more under and more forward under the horse.

At last the Terre-a-Terre straight forwards (=Mezair?) develops further, as the horses now understand better that I want them not to move forwards much. Yesterday on the way back to the stables, where the horses always quicken up a little bit, Picasso offered me of his own volition in this gait in a 45° degree angle to his "good" side, very calm and leger, eight leaps sideways, holding his body and neck straight: probably for avoiding me to get the idea to let him leap sideways on his stiff side, as he doesn't move well to his stiff side when wanting to reach a place fast. Trying afterwards to do this on his stiff, left side, he became very entier, went against the right heel and switch and became on the right side very constrained/tight (= bent the whole body and neck maximally to his right side). So in this gait anew a lot of gymnastication awaits us!

Update 03.03.2018: Tambourine movement

The Semi-Boquet grip of the switch-fist (see 01.Nov.17)

gets finer more and more: For the swinging out of the horse's hind it's not necessary anymore to put the switchhand before or behind the rein-hand: now I can leave it beside the rein-hand, it works solely by the rotation of the fist in the carpal joint. To swing the horse's hind to the left, I swivel the switch-hand to the left, so that the knuckles of the switch-fist point to the left, to swing the horse's hind to the right, I swivel the switch-fist to the right, so that the knuckles point to the right: the movement is simialr to that of hitting a tambourine against the other hand for sounding it's jingles. Thus I initiate a volte to the left by turning the switch-fist to the left for one to two steps, holding this stance if I want the horse to hold the haunches within the volte. If I want to lead the croupe back onto the circular track, I turn the fist shortly to the right (held longer to the right, a slight renvers occurs). During Canter on circular lines this proves to be very useful: Start with a turn to the inside for one to two canter leaps, then a short turn to the outside for stabilizing the circle-movement, then inside again for a better stepping under of the hindlegs, and so on.

It makes a very good support in the 80°-sideways, too: sideways to the left: knuckles to the left, and vice versa.

The chain of transmission from lower arm>shoulder>muscles of the back>rider's pelvis>seatbones is palpable (maybe sometime someone finds out the different participating muscles?).

Update 06.03.18: Same level as Newcastle?

At least regarding the switch wastage I feel coequal to Newcastle meanwhile: My current natural switch (an apple shoot, dried according to Bent's tutorial) I have in use since more than four months now. Newcastle/Cavendish

proudly reports in his first book, that his switches last up to three months, as evidence for his gentle treatment of his horses. One could argue, that he surely has worked more horses per day than me, on the other hand he writes, that he not seldom works 5 horses within 60 minutes, so the duration of use might be comparable, after all. AND: he always wore spurs additionally, which I have never put on for 17 months now!

In his second book,nine years later however, he writes that his switch endures 6 months, and at the end of this book he even mentions a duration of one year.... I wonder, if my little stick will keep this long?

Update 10.03.18

During my night-duty

yesterday, just as I passed Remlingen, the village where Loehneysen

wrote his „Della Cavaleria“, it occurred to me that the chapter

7 of book II of „The Cavalerice Francois“ I'm translating

currently, is actually the one Gueriniere refers to in his chapter

„Passage“!

Update 18.03.2018: The long awaited snafflecurb has arrived!

I had needed several months to realize that La

Broue’s and Gueriniere’s “Simple cannon” (ital.

translation:”simple thick pipe”) in reality is a curb with a broken

mouthpiece, and some more months to realize

that this was the most favored bit of La Broue and Gueriniere, then

several weeks of planning and scale drawing with making adjustments

to my horse's mouth-width, then some weeks of interchange of ideas until it was ready.

This snafflecurb is made with a broken mouthpiece exactly after my wishes.

From now on I will be able by twitching at the inner rein to push the

horse's lower jaw to the outside (which is the main use of a snaffle)

and just after that use the uprighting curb function.

The mouthpiece gets

thicker to the outside conically, to be sustained by the side lips of

the horse, too,so that a pull on the rein first reaches the lips and

only a stronger pull the tongue and the bars.

It was made hollow for a

smaller weight, as the old did, during the golden age of academic riding (Löhneysens called those

„Hohlbiß“). As its diameter in the region of the bars is

bigger, it is less hard on them.

Being my first bridling of

this type, I didn't dare for now, to let the lower branches be made

as long as Gueriniere and La Broue recommend, instead I tried at

first 18cm. To let the leverage not grow too great, I let the upper

branch elongate to 7cm, just as Gueriniere's (correction half a year later: they used only 6cm).

Thus the leverage grows

only from my former curb = 1:2, to 1:2.5 (with Gueriniere and La

Broue 1:3 is a normal value).

By this I gain an 1.7

times longer rein way, which means for example: from 4.4cm to 6.3cm.

That means my horse has much more time to sense a tightening of the

rein before the curb is fully engaged and also that I could ride with

a more unsteady hand.

The weight of this

prototype is, despite the longer branches, the same as that of a

short dressage curb plus snaffle-bit, or of one of the heavier

El-Mosquero curbs.

The curb tells the rider

similarly as with the Renaissance-curb exactly the moment it begins

to take effect, and after short probing I had learned how to twitch

at the inner rein. The positioning of the head then is actually as La

Broue describes: nearly only the head is positioned, with only a

slight bending of the neck. Showing the horse additionally the switch

on the outside led to a more rounded neck as before with my old curb,

and the muscle bump behind Picasso's atlas was gone, and I hope very

much, it stays this way!

One drawback: the little

chainette, holding the lower branches together to prevent the upper

branches leaning into the teeth of the horse and also the long lower